Readings:

[Exodus 24:12-18]; 2 Peter 1:16-21; Matthew 17:1-9

As Episcopalians, we’re fortunate enough to get to celebrate the Transfiguration twice in our liturgical year - once on the last Sunday before Lent, often known as Transfiguration Sunday, and then again on August 6, the Feast of the Transfiguration. It’s nice today to think about August – about long summer days and even sweltering heat as we feel the brunt of another ‘polar vortex’, but there is something peculiar and special about Transfiguration Sunday.

Today’s transfiguration comes at the end of the season of the epiphany, at the end of a long and particularly arduous winter, on the threshold of lent. This year, Christmas and Epiphany seem like long forgotten memories, buried under the snow and ice that have been a near constant presence. There is a hope that spring lurks just around a corner, but on a day like today, spring shows no sign of hurrying. Liturgically, we are at a threshold, or, as one of my priests calls it, a hinge day. A hinge between the seasons of epiphany and lent, but more than that, a hinge between heaven and earth. That’s what we glimpse at the transfiguration, a disruption of the norm and a supernatural event that causes fear in the disciples.

In the icons of the transfiguration, Jesus is usually depicted standing between Moses and Elijah, enshrined in gold and light on the mountaintop with rays of light emanating force, piercing the disciples. In contrast, Peter, James and John are shown lying down or with their faces turned away. We glimpse a moment of liminal space, a moment of transition and transformation and we become acutely aware that something is happening. Something is happening and we are invited to be transformed.

In the first reading, we are called to be attentive to the prophetic message, “as a lamp shining in a dark place” until the day dawns and the morning star rises in our hearts. There is a feeling of waiting, of expectation, of hope in spite of the darkness. Peter, James, and John needed this hope. Six days earlier, Jesus had told his disciples that he would be handed over to the chief priests, killed and raised up on the third day. Difficult news for anyone to swallow. It is not difficult to imagine the sort of darkness the disciples were living in – having to come to grips with the revelation that their beloved teacher would be taken from them and killed. At the same time Jesus was asking them to take up their cross and follow him. We can imagine the feelings of fear, hopelessness, betrayal…through this, Jesus asks his disciples for acceptance of what is to come.

And now, Jesus takes Peter, James and John with him up on a mountain, apart from the others and is transfigured before them – as if they didn’t have enough to deal with. But this clearly supernatural event only gets better. Out of nowhere, Moses and Elijah appear, talking with Jesus and then a voice emerges from the heavens, “This is my Son, my Beloved, with whom I am well pleased, listen to him.” The disciples naturally fall to the ground in fear and it is Jesus who rouses them, reassuring them and telling them to not be afraid. It might not be only fear that causes the disciples to fall down and turn away, but the knowledge and awareness that they are participating in something greater, something beyond their wildest imagination. They know they are being invited into transformation.

Who are these words from heaven for? In the disciples, they seem to cause more fear than anything. Perhaps it is Jesus himself who needs to hear these words, this reassurance of his father’s love, of approval, of his mission. Despite the supernatural nature of the transfiguration, perhaps this is a moment where we see Jesus’ humanity bleed through. Aware of the task before him, the difficulty of accepting what he is called to do, he takes some of his friends and goes up on a mountaintop to pray. And what is the result? Two of prophets come to speak with him and his father’s voice booming from the heavens.

We know what comes next. The forty days of Lent, the triumphal entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, the last supper, the crucifixion and eventually the resurrection. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Let’s take a moment to stand here on the mountaintop, to consider our own selves on the brink of transition – transition into a new liturgical season and transition into a new space for our work. Transition is scary. New things are scary and often hard. Sometimes we don’t feel ready for the change, something we feel that we are incapable of bearing it. We so easily forget that the journey up the mountain, the journey into the wilderness, can carry with it the potential for transformation.

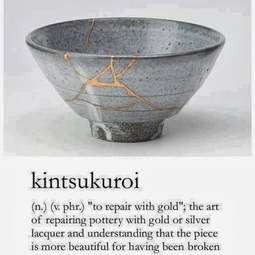

In Japanese, there is a word called kintsukuroi, which means to repair with gold. It was a word that came into mind when I read over today’s Scriptures, a word that refers to the art of repairing broken pottery with gold and silver lacquer and understanding that the pottery is more beautiful for having been broken because it is precisely those broken shards that allow the luminescent gold to show. This fits in with the transfiguration. The disciples were not perfect people. These were ordinary individuals, each with their faults, each asked to take up their cross and follow Jesus. Asked to leave behind their family and their possessions and enter into this journey with Christ. We, too, are invited into that journey, into the moment of the transfiguration. How will we let Christ transform us? How will we let him repair our brokenness with gold so that we are more beautiful for it?

- Kori Pacyniak

RSS Feed

RSS Feed