As I watched, riveted, my stomach bound itself in knots that lasted for weeks. I had no words to describe my struggle as a tomboy striving to find my way into a female adolescence without sacrificing my gender authenticity, an identity I would eventually refer to with such terms as transgender, genderqueer, ftm (female-to-male). Where language was unavailable, images and stories helped a great deal. Although Shen Te/Shui Ta was much more gender polarized than I felt (her femininity much more feminine than mine ever was, for starters), they came to symbolize my own struggle.

This play launched my mom and me into a conversation that continues to this day. At the time my mom, who was doing her doctorate in psychology, wondered if Shui Ta was for me akin to my catcher’s mask (I played catcher in Little League and Softball teams for years—that’s me above catching in my first little league game). The implication was that I somehow used masculinity as a shield. No doubt there was some truth to that. And yet, the fuller truth felt more complicated and inchoate. Being catcher-- mask or no-- felt grounding. I liked being able to survey the whole and help shepherd the action as it unfolded. It felt like home. Yet, if this subject-position was a mask—the logic went-- then it must have been merely expedient, self-denying, defensive or even deceptive. While the two didn’t initially feel very compatible, over time I discovered that they need not be mutually opposed: I could incorporate Shui Ta into Shen Te, vice versa, or both. I could simply be myself, be at home.

The mask metaphor is everywhere in LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex) narratives. Take Malcolm Boyd’s powerful memoir Take Off the Masks! which I read as I was coming out as trans. From where I sit now I admit to a certain ambivalence about the mask metaphor. Do I think it’s good to discover and remove them? Absolutely. Liberation is a powerful thing. Yet I think we should also be wary of oversimplifying our journeys and, indeed, our psyches. In his treatise "On the Making of the Human Person" (xi.2), Gregory of Nyssa muses, “who has understood one’s own mind?” I’m with him-- a certain ongoing humility about the extent of one’s self-knowledge is always in order.

Yes, liberation is indeed powerful, but it is also never ending. And if none of us is free until all of us are, we would do well to think about our masks and their removal as always partial and always linked in some deep way to the masks of someone else. There is grave danger in their oversimplification.

I see just such a risk in the global debate—crystallized but by no means exhausted by the Anglican Communion—about homosexuality. The debate has indeed enlarged to take complex and multiple cultural and religious contexts into consideration. But it isn’t just the contexts that are varied. The entity under consideration in these contexts is manifold too. We aren’t just debating ‘homosexuality’, as if the cause of our conflict was simply gay and lesbian people but not women (of any orientation), and not bisexual, transgender or intersex people. Bishop Gene Robinson has often argued that this struggle is the beginning of the end of patriarchy. I agree, and to ignore that truth is to refuse to remove an important mask from this debate.

But I’m not sure even the term patriarchy encapsulates what Robinson is pointing at. His insight should unmask the falsity that sexual difference is always an either/or proposition—that one can be either male or female but nothing else. Built on the foundation of this either/or notion is the ‘complementarity myth’, the idea that, as ‘opposite’ sexes, men and women must only partner with one another. This is exactly the place where same sex relationships overlap with transgender lives—both transgress the sexual polarization of the human person. As long as everyone must be either/or-- or must partner with either/or-- to count as a full human being, all who find ourselves outside these boxes will be accused of inauthenticity or deception. Even inhumanity or monstrosity.

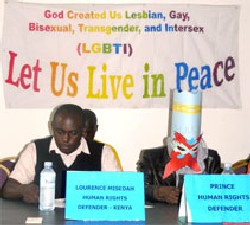

Which is what LGBTI people in Uganda are battling with particular intensity right now. To be openly LGBTor I in Uganda is to put oneself at risk of imprisonment or worse. At the end of last week a coalition called Sexual Minorities Uganda, headed by transgender-identified Viktor Juliet Mukasa, announced, “we step into the public today to give a face to the many who are discriminated against every day in our country. Some of us have brought our faces before you for you to know us. But many of us come before you today with masks to represent the fact that you see homosexuals and transgender people every day without realising that it is what we are. We do not harm anyone. We are your doctor, your teacher, your best friend, your sister, maybe even your father or son.”

The combination at this press conference of masked and unmasked people demonstrates the complex, bewildering matrix that queer people grow up having to navigate. Like Sandi Dubowski’s masterful film Trembling Before G-d, a must-see documentary which tells stories of Orthodox Jewish gay and lesbian people, the masked and unmasked activists of Uganda rendered their own invisibility visible.

Amazing how such intricately shadowed lives are also so very ordinary. It should go without saying—and yet, as Mukasa indicated, it does not-- that LGBTI people take up all sorts of vocations. Over the past two weekends the Boston Globe Magazine has run a two-part story about a beloved physician in Somerville, Dr. Deborah Bershel, who transitioned from male to female. To me, one of the most moving moments was when Bershel described a small but significant gesture of gender affirmation from her rabbi. Would that we all could receive such spiritual support.

As the fall deadline looms for the Episcopal House of Bishops to respond to the requests of the Anglican Primates’ most recent communiqué, these voices rising from Boston to Uganda begin to unmask the polarized concept of sexual difference. What a vast wedge that mask has driven in the Anglican Communion and beyond. Sexual and gender variance is so much more complex and pervasive than the debate has begun to imagine.

Back in Uganda, Mukasa’s fundamental message was "Please, let us live in peace. Stop persecuting us. God created us this way. We are children of God as well."

Leaders from the Uganda Joint Christian Council are already rallying against the outspoken ‘homosexuals’. I wonder how the Anglican Communion will understand this “we”?

The Rev'd Cameron Partridge

For Sexual Minorities Unganda’s entire Press Release, see http://www.genderdynamix.co.za/content/view/281/204/. Gender DynamiX describes itself as “the first (and currently, the only) African based organisation for the transgender community.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed